Firstly, it seems the Guardian didn't read my last post, because they've gone and published this. I love how, when it comes to a choice between the International Energy Agency and Greenpeace on assigning the contribution shale gas has made to the US's substantial CO2 reductions since 2007, the default assumption is the Greenpeace must be right and the IEA wrong. It's not like Greenpeace have a conflict of interest in downplaying shale gas contributions to CO2 emissions reductions or anything. Meanwhile, the IEA, as an international body with a duty of care, years of experience, and who actually have environmental protection as part of their remit, can't be relied upon?

I'll let John Hanger have the last word on the matter:

http://johnhanger.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/another-analysis-of-role-of-gas-in.html

http://johnhanger.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/natural-gas-is-responsible-for-about-77.html

http://johnhanger.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/10-key-facts-to-understanding-decline.html

As usual, the doom-mongers say that shale gas can't possibly have an impact on our energy markets. Maybe their models are right, but this would completely discount the on-the-ground evidence from the US, where it's had a significant impact. But anyway, maybe there won't be enough shale gas to make a dramatic impact. But it can only help push things in the right direction - shale gas production will help stabilise volatile gas markets and reduce prices by boosting supply. This effect may be large, or it may be small, but I'd rather take my chances on a small benefit that could become a larger benefit, rather than just giving up before we even begin. And if companies want to take the risk by investigating money into shale gas exploration, that's their choice (I'm sure they did at least a little bit of research on the issue before sinking all that money in).

I should add that the rumour going round is that the next BGS shale gas reserves estimate is likely to be significantly upgraded. This is just a rumour at the moment, but it wouldn't surprise me.

BTW, I do love the contradiction inherent in so many anti-shale-gas commentaries - "shale gas would contribute considerably to our greenhouse gas emissions when we should be going renewable, but anyway there's not enough shale gas there to make an impact on our energy markets, so we shouldn't bother". Well, which is it? There's either enough down there to fry us all, or there isn't and we should be perfectly happy to let these companies waste all their money looking for something that will never be economic.

Finally, an interesting blog post from the US from someone in the heart of fracking country that is well worth a read. The author talks about how the money from shale gas exploration has helped her keep the family farm going, and about the wider economic boost that the area has experienced, while pointing out how exaggerated all of the shale gas scare stories really are.

The blog begins by talking about the new Matt Damon movie, the Promised Land, which is based around shale gas (Damon plays a company man tasked with getting the locals to sign gas leases, which goes swimmingly until all the pollution kicks off). There are some interesting rumours circulating about a final twist in the plot. Apparently, the OTT environmental campaigner turns out to be a company plant intending to discredit the environmental movement by smearing its members. I've no idea whether this will turn out to be true, but it seems pretty far-fetched to me!!! I guess we'll have to see.....

Friday, 28 September 2012

Sunday, 23 September 2012

Another predicatably one-sided Guardian article

Isn't it frustrating when an organization that you otherwise identify with can be so completely dunderheaded over certain important issues. The Green Party's anti-scientific attitudes to homeopathy and to GM foods spring immediately to mind. And once again, my paper of choice (the Guardian) prints (yet another) poorly researched and in some aspects downright false articles about shale gas and fracking. So once again, my comments:

But evidence is mounting that fracking pollutes groundwater with a witches' brew of toxic chemicals, creating imminent threats to public health and safety. It has even caused earthquakes in Ohio.One report from one test well in Wyoming. And some methane contamination from a poorly cemented well in Dimock, now dealt with and methane levels below acceptable limits once again. Does that count as 'evidence mounting'? I guess so. From several hundred thousand fracked wells across the US. No mention of the head of the EPA's views on shale gas. As for the earthquakes in Ohio - they were caused by waste-water injection, not fracking. Waste-water injection is a common practice throughout the oil industry. And if you're really against water injection, pass a regulation requiring companies to treat all their water at the surface - which is also common practice in many situations.

The detonation of explosive charges, coupled with the infusion of high-pressure fluids, fractures the shale, allowing the gas to bubble up to the surface.The 'how-shocking-is-fracking' brigade love mentioning the explosives. Sounds dangerous, right? Truth is, explosives have been used to complete oil wells for as long as for ever. The explosives are not to blow the rock apart - they are small directed charges to pierce holes in the steel well-bore casing. It is the high-pressure fluid that moves into fractures and pushes them apart. Proppant (usually sand) is then injected to keep the fractures open, allowing the gas to flow to the well, where it rises to the surface.

The components of the fluids used for fracking are considered protected trade secrets, although they are known to contain toxins. Where the fracking fluids go is a key question.The details of every chemical pumped down every well in the US is available on this website. It's getting to the point that one begins to suspect the journalists who still push the 'fracking-chemicals-are-trade-secrets' line are not just poorly informed/poorly researched, but outright promulgating lies to make their articles sound more dramatic (and thereby garner a larger following). As for this 'toxic witches' brew' - the latest fracking fluids are in fact safe to drink. Another thing that really bugs me is the use of the word 'cocktail' whenever people describe the fracking fluid (as in this 'cocktail of chemicals') - if someone handed my a cocktail that was 99% water and 1% active ingredient, I think I'd be finding a new barman!

As for where the fluids go? Between 30% to 50% come back up the well, meaning the rest is still in the ground, in the shale formation. These shale formations contain gas (of course). The gas will have been there for hundreds of millions of years. Natural gas, being buoyant and low viscosity, is one of the mobile fluids you can have in the subsurface. If the formation has been capable of trapping gas for 100,000,000 years, I'm pretty sure it can trap saline brines, which don't have any buoyancy force acting on them, and are much more viscous than gas. So in short, we know where the fluid has gone - it's trapped in the shale formation.

Fracking entered the national debate when the award-winning documentary Gasland, made by film-maker Josh Fox, showed how people living near fracking operations could easily set their kitchen tap water on fire.Gasland did win plenty of awards, but mainly for it's artistic qualities (which, fair play, is really well shot) not for journalistic integrity. No mention of the state regulation findings that the gas coming out of the 'flaming faucets' was biogenic in origin, not thermogenic, meaning that it was gas from shallow bacterial processes, not related to the shale gas at depth (they have characteristically different isotopic signatures). Methane in water supplies is a common phenomena in many artisan wells across the US, and has been for centuries. Josh Fox knows this, but didn't consider it relevant to mention in his film. Gasland is not journalism, it's storytelling. Which is fine, but the Guardian is a newspaper, so it's supposed to do journalism.

Like every good journalist, and appropriately, in this post-Citizens United era, Fox follows the moneyThat would be the money flowing into his bank account as environmental groups around the world rush to buy screening rights and speaking engagements, on the basis of his film which strikes just the right controversial, highly unbalanced tone?

As I've said a million time now - shale gas extraction IS and industrial process, and as when any industrial process starts up in a new place, there should be a fair and rational discussion to weigh the potential risks and benefits. Which is why it's disappointing that the Guardian seems to be only interested in writing about scare stories and falsehoods.

Tuesday, 18 September 2012

Shale gas and emissions of greenhouse gases - finally put to bed

Burning methane (whether from shale gas or elsewhere) produces half as much CO2 per unit energy as coal. So switching from coal fired power stations to gas leads to significant reductions in CO2 emissions. This is why 5 to 10 years ago, every environmentalist was calling for a 'golden age for gas'.

However, methane itself is a potent greenhouse gas: 75 times more potent than an equivalent mass of CO2 over 20 year timescales, 20 times more potent over 100 years (the potency goes down over time because methane comes out of the atmosphere faster than CO2, meaning that if equivalent masses are released, the methane gets removed faster). So, if while extracting methane you end up releasing lots of it to the atmosphere, it can cause more warming than you save by burning gas instead of coal.

This was the suggestion made by Howarth, a professor at Cornell. Since then, the debate has rumbled on, with a number of rebuttals, including from Howarth's colleagues at Cornell. Nevertheless, I still see the 'shale gas is as bad as coal for the climate' line being trotted out regularly in news reports and discussions about shale gas.

However, I think the shale-gas and climate change issue can finally be put to bed. A new report for the European Commission has been produced, looking at the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions for European shale gas. It runs to 158 pages, so I can't tell you I've read it all, but here are the highlights. These number are based on an assumption of a loss of 1 - 5% of the methane at the well head during the fracking process - generally accepted numbers for most people. So, what does that mean?

1.) Shale gas isn't as good as conventional European gas (i.e. from conventional fields, mainly in the North Sea and onshore Netherlands). GHG emissions from shale gas are 4% - 8% higher than conventional gas. But that was hardly surprising. However, our conventional gas fields are all beginning to run out.

2.) European shale gas may well be better than gas piped from Russia or Algeria, or shipped in as LNG. Obviously, it takes energy to transport gas from these distant places in to Europe, increasing the amount of GHG emitted per unit of energy you generate. So European shale gas has emissions 2% - 10% lower than piped Russian or Algerian gas, and 7% - 10% lower than gas imported as LNG. This is REALLY interesting - it says that if we plan to burn gas (even as a backup to large wind farms and solar), it should be our home-grown European shale gas, rather than gas imported from afar (not to mention the geopolitical implications of having to give Mr Putin et al all our money).

3.) Shale gas is significantly better than coal. Not surprising to people who have studied that numbers from previous studies, but hopefully if enough reports say this, I'll get to stop reading in newspapers and environmental publicity that shale gas is more dirty than coal. Emissions from shale gas-fueled electricity are 41 - 49% lower than emissions from coal. That's a really significant chunk we could take out of our GHG emissions just by switching from coal fired power to gas.

And is there evidence to back this up? There sure is! US CO2 emissions are plummeting as cheap shale gas displaces coal from the electricity generation market. While some of the 9% decrease in CO2 emissions can be attributed to improved efficiency reducing demand, and increased renewable energy sources, the major bulk (77% by John Hanger's estimate). Wouldn't it be nice if we could have cheaper energy bills while reducing our CO2 emissions over here in Europe?

However, methane itself is a potent greenhouse gas: 75 times more potent than an equivalent mass of CO2 over 20 year timescales, 20 times more potent over 100 years (the potency goes down over time because methane comes out of the atmosphere faster than CO2, meaning that if equivalent masses are released, the methane gets removed faster). So, if while extracting methane you end up releasing lots of it to the atmosphere, it can cause more warming than you save by burning gas instead of coal.

This was the suggestion made by Howarth, a professor at Cornell. Since then, the debate has rumbled on, with a number of rebuttals, including from Howarth's colleagues at Cornell. Nevertheless, I still see the 'shale gas is as bad as coal for the climate' line being trotted out regularly in news reports and discussions about shale gas.

However, I think the shale-gas and climate change issue can finally be put to bed. A new report for the European Commission has been produced, looking at the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions for European shale gas. It runs to 158 pages, so I can't tell you I've read it all, but here are the highlights. These number are based on an assumption of a loss of 1 - 5% of the methane at the well head during the fracking process - generally accepted numbers for most people. So, what does that mean?

1.) Shale gas isn't as good as conventional European gas (i.e. from conventional fields, mainly in the North Sea and onshore Netherlands). GHG emissions from shale gas are 4% - 8% higher than conventional gas. But that was hardly surprising. However, our conventional gas fields are all beginning to run out.

2.) European shale gas may well be better than gas piped from Russia or Algeria, or shipped in as LNG. Obviously, it takes energy to transport gas from these distant places in to Europe, increasing the amount of GHG emitted per unit of energy you generate. So European shale gas has emissions 2% - 10% lower than piped Russian or Algerian gas, and 7% - 10% lower than gas imported as LNG. This is REALLY interesting - it says that if we plan to burn gas (even as a backup to large wind farms and solar), it should be our home-grown European shale gas, rather than gas imported from afar (not to mention the geopolitical implications of having to give Mr Putin et al all our money).

3.) Shale gas is significantly better than coal. Not surprising to people who have studied that numbers from previous studies, but hopefully if enough reports say this, I'll get to stop reading in newspapers and environmental publicity that shale gas is more dirty than coal. Emissions from shale gas-fueled electricity are 41 - 49% lower than emissions from coal. That's a really significant chunk we could take out of our GHG emissions just by switching from coal fired power to gas.

And is there evidence to back this up? There sure is! US CO2 emissions are plummeting as cheap shale gas displaces coal from the electricity generation market. While some of the 9% decrease in CO2 emissions can be attributed to improved efficiency reducing demand, and increased renewable energy sources, the major bulk (77% by John Hanger's estimate). Wouldn't it be nice if we could have cheaper energy bills while reducing our CO2 emissions over here in Europe?

Tuesday, 11 September 2012

Export and Import: CO2 emissions and shale gas

When we talk about climate changing greenhouse gas emissions, we often tend to look at the emissions on a country-by-country basis. This is a list on a country-by-country basis.

These figures are calculated based on the amount of fossil fuels burned within a country's borders - how many coal fired power plants and diesel trucks they have pumping out CO2. But is this really the most appropriate way of considering these figures? Surely what matters is who the fossil fuel is burned for!

China, at 7 billions tonnes of CO2 per year, now tops the world CO2 emission rates. However, a significant proportion of what China produces is in fact consumed by us, here in the west. As a family growing up we used to joke that Santa must live in China, because that's where it says all the toys were made. So do some of these emissions really belong to us? To whom do we apportion the emissions? To the Chinese who are making the products, or to us, who are consuming them? It's not an easy question really. But lets face it: the fossil fuels are being burned for our benefit, just in a different country.

This brings us on to the potential importance of shale gas. Early estimates show that China could have significant shale gas resources. Energy companies are already beginning to invest. Production of Chinese shale gas would displace coal energy production, slashing CO2 emissions as we have already seen in the US. Encouragement of shale gas technologies will therefore play a vital role in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.

And let's face it, it's the global emissions that count for global warming. We could cut UK emissions down to 0, but that wouldn't stop climate change unless China, the US, India et al. cut their emissions as well. And no matter how many wind turbines we build on Donald Trump's golf course, that won't help us reduce the CO2 that is attributable to us but being emitted in China.

What we can do is what the UK has always done: use it's world leading engineers and scientists to develop and improve new technologies - in this case safe extraction of shale gas - enabling us to sell our expertise to the rest of the world. This would help our economy, and it's the only way we can reduce the CO2 emissions that are being produced for our benefit inside countries like China.

Postscript: Thanks to Owain S for drawing my attention to this issue

These figures are calculated based on the amount of fossil fuels burned within a country's borders - how many coal fired power plants and diesel trucks they have pumping out CO2. But is this really the most appropriate way of considering these figures? Surely what matters is who the fossil fuel is burned for!

China, at 7 billions tonnes of CO2 per year, now tops the world CO2 emission rates. However, a significant proportion of what China produces is in fact consumed by us, here in the west. As a family growing up we used to joke that Santa must live in China, because that's where it says all the toys were made. So do some of these emissions really belong to us? To whom do we apportion the emissions? To the Chinese who are making the products, or to us, who are consuming them? It's not an easy question really. But lets face it: the fossil fuels are being burned for our benefit, just in a different country.

This brings us on to the potential importance of shale gas. Early estimates show that China could have significant shale gas resources. Energy companies are already beginning to invest. Production of Chinese shale gas would displace coal energy production, slashing CO2 emissions as we have already seen in the US. Encouragement of shale gas technologies will therefore play a vital role in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.

And let's face it, it's the global emissions that count for global warming. We could cut UK emissions down to 0, but that wouldn't stop climate change unless China, the US, India et al. cut their emissions as well. And no matter how many wind turbines we build on Donald Trump's golf course, that won't help us reduce the CO2 that is attributable to us but being emitted in China.

What we can do is what the UK has always done: use it's world leading engineers and scientists to develop and improve new technologies - in this case safe extraction of shale gas - enabling us to sell our expertise to the rest of the world. This would help our economy, and it's the only way we can reduce the CO2 emissions that are being produced for our benefit inside countries like China.

Postscript: Thanks to Owain S for drawing my attention to this issue

Saturday, 1 September 2012

Latest shale gas developments around the world

An update on the latest shale gas developments around the world:

UK: Cuadrilla have applied to drill their first lateral well on the Fylde peninsular. Lateral wells go down into the ground but bend to go horizontally along the rock strata. This is the first drilling to go ahead after the 2011 tremors. It's good to see things getting moving again after a long pause. I'm assuming that this well will aim to test the productivity of the Bowland shale - whether they can get decent and sustainable gas flow rates.

China: Shell plan to invest $1 billion a year in Chinese shale gas. This is really significant news! Although not well explored, China is likely to have significant volumes of shale gas resource. China is currently the world's largest CO2 emitter, mainly from the thousands of coal power plants built to power and growing and increasingly wealthy population. If shale gas can take off, replacing coal in electricity generation, and we see a similar rate of progress to that seen in the US, then these emissions could be substantially reduced over quite a short period (as well as significant improvements in air quality which, as anyone who's been to Beijing in the last 10 years can tell you, is a serious problem there). China is an ideal place to exploit shale gas - wide open continental interiors, sparse population, and a government accustomed to developing infrastructure on a large scale.

Argentina: It looks like Argentina may have made some significant shale gas and shale oil finds. Shale oil is important, because it is much more valuable than gas, so it entails a greater profit if shale oil as well as gas is found. Worrying if you live on the Falklands though, the thought of Argentina getting wealthy on the back of shale oil....

US: Gas drilling is set to resume in Dimock. Dimock has been the headline case for the US anti-fracking movement, the ground zero of fracking-induced pollution. In 2009 a poorly cased well allowed methane migration into a fresh-water aquifer (note that methane was the only thing that migrated, no fracking fluids were ever found to be migrating. Drilling was then suspended and Cabot (the operating company) have been subject of a number of lawsuits. Now things have been settled, the well has been recased, and methane levels in the aquifer are back to normal levels, and drilling is about to restart. The eyes of those both pro and anti fracking will be on Dimock again, to see if the drilling company can get it right this time.

UK: Cuadrilla have applied to drill their first lateral well on the Fylde peninsular. Lateral wells go down into the ground but bend to go horizontally along the rock strata. This is the first drilling to go ahead after the 2011 tremors. It's good to see things getting moving again after a long pause. I'm assuming that this well will aim to test the productivity of the Bowland shale - whether they can get decent and sustainable gas flow rates.

China: Shell plan to invest $1 billion a year in Chinese shale gas. This is really significant news! Although not well explored, China is likely to have significant volumes of shale gas resource. China is currently the world's largest CO2 emitter, mainly from the thousands of coal power plants built to power and growing and increasingly wealthy population. If shale gas can take off, replacing coal in electricity generation, and we see a similar rate of progress to that seen in the US, then these emissions could be substantially reduced over quite a short period (as well as significant improvements in air quality which, as anyone who's been to Beijing in the last 10 years can tell you, is a serious problem there). China is an ideal place to exploit shale gas - wide open continental interiors, sparse population, and a government accustomed to developing infrastructure on a large scale.

Argentina: It looks like Argentina may have made some significant shale gas and shale oil finds. Shale oil is important, because it is much more valuable than gas, so it entails a greater profit if shale oil as well as gas is found. Worrying if you live on the Falklands though, the thought of Argentina getting wealthy on the back of shale oil....

US: Gas drilling is set to resume in Dimock. Dimock has been the headline case for the US anti-fracking movement, the ground zero of fracking-induced pollution. In 2009 a poorly cased well allowed methane migration into a fresh-water aquifer (note that methane was the only thing that migrated, no fracking fluids were ever found to be migrating. Drilling was then suspended and Cabot (the operating company) have been subject of a number of lawsuits. Now things have been settled, the well has been recased, and methane levels in the aquifer are back to normal levels, and drilling is about to restart. The eyes of those both pro and anti fracking will be on Dimock again, to see if the drilling company can get it right this time.

Friday, 24 August 2012

My latest outreach attempt:

Good afternoon dear readers, I trust you are enjoying your Friday afternoons. If time is passing slowly (and with the potential distraction of cricket rained off again) then you will be in need of a procrastination measure. In which case you can spend 100 seconds of your time watching my latest outreach attempt - explaining fracking and CCS in 100 seconds for Physics World's 'Physics in 100 seconds' feature. Enjoy.......

Thursday, 16 August 2012

Bought and paid for?

If shale gas companies are involved in funding research, is that research intellectually compromised?

It's a really important question - there have been several favourable reports about shale gas recently, and most have some connection to the oil and gas industry, as reported in this Guardian article. Does this mean we can't believe what is in the reports - are they intellectually compromised?

This is a particular issue for me in my own work. My funding situation is a little complicated. We have an industry funded research group at Bristol, which funds most of my office-mates. However, I myself am funded on a NERC grant (that's the government). However, part of the NERC grant involves being given data for free by BP. So although they're not giving me cash, there is a connection there, and the data is given in lieu of a cash payment that would otherwise have to cover 25% of my grant. So while I'm not directly getting any money from industry, there are certainly strong connections there.

But how does this affect my work? I can honestly say it doesn't affect it one bit. I've never hidden or not published data in case of embarrassing a sponsor. I've never massaged figures. The very idea that I would is completely offensive!

(Not that I would, but I guess I've never had to, because I've never come across data showing a problem with shale gas.)

I think some people miss the point as to why companies generally fund research. Usually, funding academic research is not a public relations exercise - they have different departments, different budgets and different people for that (besides - have you met academics - PR is not our strong point). They usually fund academic work because they want to get to the bottom of a question that is perhaps too broad in scope, or too specialised, for them to do in house. They fund academics because they want answers, not yes men. I think we'd be more likely to lose our funding if we were found to be making data up to cover a problem, than we would be by publishing about a particular issue.

Besides, it's not really surprising that authors of reports on shale gas have industry connections. If you had no industry experience, how on earth would you have the knowledge to write a report on shale gas? Do you know about well casing, drilling methods, pressure-based and microseismic monitoring methods? If you do, chances are you've worked in industry, because it's the only place you can learn about these things. And if you don't how exactly do you intend on writing accurately about shale gas extraction?

So in reality, beyond the shock headlines of Guardian-land, it's not surprising that most of the reports about the shale gas have some sort of connection with the shale gas industry. Most reports about wind energy come from groups that have some involvement in wind turbine manufacturing or design. In fact, most of our information about wind seems to come from RenewablesUK, and they're not likely to be unbiased are they?

Indeed, the chair of Parliament's Energy and Climate Change committee is Tim Yeo, who receives something like £140,000 a year from renewable energy firms. This isn't some independent university report, which we (and our policy-makers) are free to read or ignore as the will. This is a parliamentary committee set up to advise parliament on energy issues, and it's chaired by a man who stands to gain considerably by promoting wind energy over other generation methods. Yet because it's wind, we're ok with this (well, except for the Mail and Telegraph, of course). Can you imagine the outrage if it transpired that the chair of such a committee was trousering hundreds of thousands of quid from Exxon?

And what about reports funded by environmental pressure group? Reports critical of shale gas have come from the Park Foundation, the Cooperative, and you won't be surprised to hear that Greenpeace are not fans. But do these reports have an underlying motive pushing them towards a certain conclusion before the study even starts? They don't have a profit motive as such, so surely they'll be unbiased? Not really. Just because there's not an immediate bottom line, organisations like Greenpeace have a reputation to uphold, and followers to keep happy.

Without the support of these followers, they'd become meaningless. And can you imagine the response of the Greenpeace faithful if they came out and said - 'you know, we've looked at all the evidence, and on balance, exploiting shale gas is the best thing we can do for the environment right now, because it's better than mining and burning coal'? Of course they can't say that - their supporters would be livid, and would leave in droves. For an environmental organisation to say that is as likely as an oil company saying 'do you know what, this whole shale gas thing is just too risky, we're not going to chance it' - it's just not going to happen. So I don't think a report funded by an environmental organisation is any more likely to be unbiased than a report from an oil company. The only difference is that an oil industry report is more likely to have up-to-date information to hand, helping to avoid this kind of fiasco.

So if all reports have the possibility (or even probability) of bias, who do we believe? How do we get anywhere? I guess the key is that ultimately, all reports have to be based on data. And sure, you can try to use statistics to get the result you want, but ultimately, data will show one way or the other. So the data is pretty clear that fracking caused 2 small earthquakes near Blackpool (earthquakes are notoriously difficult to hide, you see). However, we can see that for all the fracking in the US, no notable earthquakes have been caused (there have been quakes caused by re-injection of waste water in deep aquifers, but this is a different problem and one not unique to fracking).

We know that the EPA has shown evidence of water contamination at Pavilion (WY) from fracking. Pavilion is a difficult case, because the reservoir is much closer to groundwater aquifers than most typical shale reservoirs, so perhaps this isn't so surprising. In Dimock (PA) there was a methane contamination in 2009. After repairs to a well, all levels of contaminants have returned to normal. And that's pretty much it, two incidents for hundreds of thousands of fracks. Meanwhile, US CO2 emissions are plummeting as shale gas is used instead of coal in electricity generation.

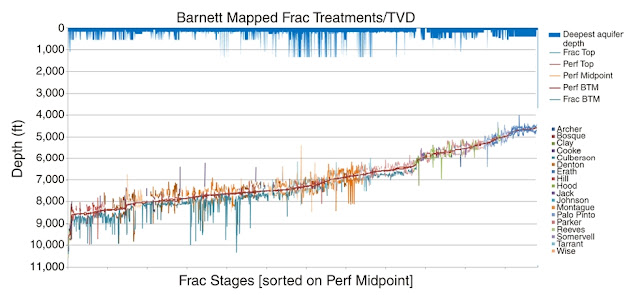

Finally, the evidence from my speciality, microseismic monitoring is pretty unequivocal. This image shows the depth of every microseismic event in the Barnett shale. The coloured lines track where the fractures have gone during fracking. As you can see, even the shallowest fractures are very far away from any potential water source (the blue bars at the top). This is hard data - you can't fake this. But don't expect to see this picture in any Greenpeace report (or Josh Fox film) any time soon.

As I've mentioned before, the anti-shale groups have struggled to find proper geologists to support their cause. Academics, yes - but they tend to be atmospheric chemists, climate change specialists and biogeochemists, not proper geologists. I think that this is because it might take a geologist to fully understand how difficult it would be for contaminants to rise from the reservoir through 2-3km of impermeable rock (with little or no driving force, given that fracking fluid is less buoyant than gas) to reach potable water supplies. Usually, if there's legs in an idea, you can usually find someone to run with it. And I think that is probably the most encouraging thing I can say about shale gas - there are hardly any serious geologists who have a problem with it.

Update [19.08.2012]: Thanks to my favourite (only) commenter Owain S for this, but I've just been perusing the links he posted, leading to something that has left me gobsmacked. Despite making hundreds of thousands from wind energy investments, while championing wind subsidies in his role as Chair of the Energy and Climate change committee, Tim Yeo is in fact opposing the development of turbines in his own constituency, on the grounds that they are unsightly and would spoil his view. Wow! Just, wow! That is an incredible level on hypocrisy - happy to foist turbines on everyone else, but not in his back yard please.

Saturday, 11 August 2012

Misleading shale gas videos

Here's a great pair of videos to examine some of the highly misleading scare stories put out by the anti-fracking activist community.

Here's the first video. It consists of infra-red videos of drilling natural gas platforms, and it purports to show large quantities of fugitive methane emissions from well heads. Large amounts of fugitive methane emissions would have an impact on global warming, as methane is a potent greenhouse gas, as well as having impacts on local air quality. So if these fugitive emissions are true, this would be worrying.

The video is narrated by Robert Howarth, a professor at Cornell who has gained a fair bit of notoriety for some widely debunked anti shale gas papers.

So what are these gas-like emissions that appear to be rising from these drilling platforms? It turns out, these are just exhaust from the diesel generators and pumps working on the sites. This video explains all. There are clear differences between what methane emissions look like and what hot diesel engine exhaust emissions look like, and these are clearly the latter.

I found it really hard watching to be honest - it becomes apparent that Howarth and the CBF have deliberately and intentionally lied about what the emissions are in order to produce a scary, high-impact anti-shale-gas video. It's shocking, frankly, and unfortunately it's what we've come to expect in the highly polarised shale gas debate.

Meanwhile, of course, increasing natural gas use has lead to significant drops in US CO2 emissions since 2008 back to 1992 levels, while in Europe our energy policies have actually lead to an increase in coal use.

As I've said numerous times, there is a rational debate to be had about shale gas extraction. For example, as we can see in the videos, they require large diesel engines for pumping during drilling and fracking. This is an industrial process, and when any industrial practice moves into a new area it should be after a frank and open debate with people living in that area (and not activists bussed in from Brighton), including both the positives (the economic benefits to the region, a cheaper and less CO2-intensive energy source) and the negatives (increased truck traffic, water use, unsightly rigs, the potential for low-level seismicity). Unfortunately, the debate about shale gas has already become too polarised, and blatently misrepresentative 'scare' videos like this one really don't help with anything.

The shale gas revolution - infographic

Apologies for a little barren, non-blogging spell, I've been on holiday in Iceland. It's truly spectacular - a really beautiful country. I'd recommend it to anyone. Anyway, just a quick post before I write a longer post a little later - consider this the blogging equivalent of an amuse bouche. A friend found this natural gas infographic on mining.com - it really sums up nicely the affect that shale gas has had on the US energy industry. Update - blogger being a bit rubbish, I can't find a way to upload the image with the size and quality needed to see it, so link to the image here.

Thursday, 19 July 2012

The Open Access Publishing Revolution

After a campaign championed by the Guardian, the UK research councils have announced a move towards open-access publishing. There's currently a huge amount of debate within the academic community about the best model for publishing.

Currently, academic publishing is dominated by the large publishing houses - Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell, Springer, etc. When I write a paper with new and interesting scientific findings, it needs to be published to enable my fellow scientists to read about what I've done, enabling them to use my findings in their research. The typical business model for a journal is as follows: most journals do not charge me a fee to publish (some do, but it's usually not too onerous). They make their money by charging people to read them. University libraries will buy subscriptions to the journals (usually they will buy 'bundles' allowing subscriptions to an entire publisher's catalogue), allowing all academics at the university to read the article. Meanwhile, a company wanting to access the research is more likely to pay the upfront fee for an individual article, which is usually about £30. Similarly, private individuals wanting to access the research will have to pay the £30 fee per article.

The dissatisfaction with the current model stems from the fact that the majority of scientific research in this country is funded by the tax payer (including my own). How, then, can it be fair that tax-payers are paying once to fund the research (out of their tax money), and then have to pay again as individuals to read the research? Many in the academic community view this as a morally untenable position - the public should have free and unfettered access to the results of all taxpayer-funded research (and when you read the comments sections on various websites, you really do get a sense of moral outrage).

I disagree with this argument. There are many things that my tax-money pays for, yet I can't just access for free. Our taxes go to the BBC, but I still have to buy a license fee to watch it! Taxes fund the NHS, but I still have to pay a fee for my prescriptions. Let's face it, some of my tax money goes to the army to buy tanks - that doesn't mean I have a right to turn up at the gates of my nearest barracks and demand a ride on a Cheiftain!

But, under the pressure of the academic community, the government, via the UK funding bodies, has buckled to pressure and is now about to make things far worse. They are planning to mandate that we publish only in open access journals. The business model here is that, rather than a 'reader-pays' model, we switch to an 'author-pays' model. Journal articles are made available for free, so instead authors are charged a much larger amount (typically £2000 or so). As far as I am concerned, this is a very bad publishing model!

What are the benefits of a so called 'gold' open access publishing model, where the author pays? Well, the sole benefit is that anyone, anywhere, can read your article for free. The negative is that this could add an extra 5 to 10% to the costs of of UK research. For example, last year NERC (my funding body) spend £180 million on research, and about 5,000 papers we published as a result. With gold open access of £2000 per article, this would be an extra £10 million, so just over 5%. Of course, the funding councils are not being given any extra money, so that means they will be able to fund 5 to 10% less research. In a time where our science budgets are increasingly stretched, and grant money harder and harder to come by, can this really be a good thing?

Secondly, we must consider the pressures this will place on the publishing industry. Currently, in a 'reader pays' model it is in the publisher's interest to publish only the best and most relevant research. A journal cannot afford to waste money publishing work that will not get read. Therefore, the commercial pressure is on journal editors to accept only the best work. Under an 'author pays' system, the only commercial pressure on the journal is to publish as much as possible. Quality is no longer a driving factor, because it doesn't matter whether things get read, all that matters is that there's lots of papers. So an author-pays model will simply lead to a significant reduction in the quality of articles that journals are prepared to accept. Putting this as simply as possible, there would be no reason for a journal to ever reject any paper, ever. I don't want to spend my time wading through a ton of crap papers to find the one or two good ones that I need. I want a journal to have already taken editorial decisions to only bring the ones that are of the highest quality to my attention.

What about the effects on libraries? Perhaps the libraries would be able to save money, because they wouldn't need to pay for so many journal subscriptions, and the money saved could be transferred over to cover author charges. However, this wouldn't cover all the back issues to which scientists need to access. Nor would it remove the need to subscribe to international journals to access work from people in other countries. Science is an international effort, so if the UK does something in isolation, it won't affect the need to pay subscription fees to read about work from every other country in the world.

Finally, what will be the impact on publishing academics. Obviously, the only barrier to publication will be money, so if you have money, you can publish, while if you don't, you can't. The model in mind is that university faculties will have central pots of money to pay for open access publication. So who will get the money for publication - the junior PhD student who has made a cool new finding, or the senior professor with his hand on the purse strings? At present, the quality of the paper is the sole deciding factor in where a paper is published. Under the proposed system, the deciding factor will be money. This would NOT be a fairer system, if would be significantly UNFAIR! I cannot understand how academics can be in favour of such a system.

The other proposed model is so called 'green' open access. This model takes the money out of the system entirely. Academics post their own content on their own websites (or possibly on a university-wide archive) or on archive sites such as the arXiv. To a certain extent, this system is already active, because many authors do post their work onto arXiv, and do post their papers on their own websites. Many academics see this as the model to which we should evolve. However, I think this is somewhat misguided, because the currently green open access exists off of the back of the mainstream publication industry, it cannot exist without it. Firstly, note that many green open access sites are heavily subsidised (as arXiv is by Cornell, for example, to the tune of about $500,000 per year).

More importantly, if I publish a paper in arXiv, it is not peer reviewed. Peer review as a process is vital to science, it makes sure only reliable results are published, and removes all the dross. I know it's not perfect, but it's the best system we have. The only way to get things peer reviewed is to submit them to journals, where they will undergo the full editorial process. Currently, journals are happy to provide this service, and publish the paper as their content, while allowing re-prints to be republished on author's websites, because it's not done widely enough to effect their margins. Just because a certain number of authors have put their papers on other websites, libraries are still forking out for subscriptions. If green open access became so widespread that it began to impact on the bottom line, I expect journals would begin to clamp down.

I guess this all comes down to whether publishers provide a useful service, or can we do without them. If they provide a necessary service, we should be prepared to pay for that service accordingly. If they do not, or if we believe we can achieve the same effects more cheaply, we should attempt to do so. Paraphrased from a comment on this blog, we need journals to provide (1) a decent and enforced peer review system, (2) an editorial system which can reject (or grade) papers (which provides quality control and therefore acts as a marketing tool) (3) a publishing system and (4) a citing system. The need for peer review is obvious, as is the need for a publishing system. Both cost money to administer. It is not free to put things on the internet - arXiv needs half a million dollars a year to function.

The need for a citing system is a key problem for green open access. Say I publish my paper, and put it on my website. Will it still be there in 15 years time when I have long moved on, or will a searcher simply find a broken link? It's vital that researchers can access older papers - journals provide the means of archiving them and an easy means to index and access them. This would not be possible with authors sticking their papers wherever under a green open-access system. The editorial and grading system is also vital, for both author and reader. Rightly or wrongly, as academics we are graded on the quality of papers we produce. When we can post whatever we like in an open-access mega-journal, it becomes very difficult to assess the quality of a academic's output (perhaps this is why so many favour this system). More importantly as a reader of papers, I much prefer to be able to look at the monthly output of my favourite journals, scroll through the list of papers that they have (which is a manageable list), rather than dive into a mega-journal and have to sift through all the dross to find some good papers. I'd rather pay an editor to do that for me.

Given these needs, how much will all these things cost? Let's imagine a typical medium-sized journal. They'll probably have about 5 staff: a senior editor to lead the editorial direction of the journal; two publishers to facilitate the peer review process - selecting the reviewers for each paper (or rejecting the really rubbish papers without review; an admin; and a guy to do the publication side of things. Plus within the publishing house they have the IT support and the rest. Let's say it costs £500,000 a year to cover everyone's salary, pension, computing costs, web archiving costs and the rest. This is a complete guess, but it doesn't seem like an exorbitant amount, right? In fact, this is probably on the low side. Well, for a medium-size journal publishing 500 papers a year, that's a cost per paper of £1000. So this must be paid either by the author, or through subscription. I don't see green open access as long term sustainable except on the back of a healthy publishing industry to bear most of the costs. As a commentor on the Guardian website put things rather well of the problems we'd face if we abandoned journals:

My thoughts on this are formed partly by my experiences while working as an intern at Shell. During my 3 months there, I must have downloaded at least 20-30 papers, paying the upfront costs each time. That comes to about £600-£900. Shell have a library system where you request a paper and they go off and get it for you, and they don't even (appear to) worry about the costs. I've no idea how much the average Shell employee downloads papers, but these are science-intensive companies, so I bet it's quite a lot. Whenever I meet employees, they all seem fully up-to-date with the latest research, so they must be reading it. This is money that goes back into the academic system, helping to contribute to a healthy publishing system that is necessary for research. And Shell are going on to use this research to make money. Under an author-pays model, they wouldn't have to contribute anything.

So what about the poor UK 'citizen-scientists', working independently, who want to read the latest research papers. These people are usually all over the Guardian comment pages complaining that they can't access research without paying. My first opinion is that they can't be that keen to read it - if you want to read a paper but can't find a non-paywall copy, your first port of call should be to email the author, who will likely be more than happy to furnish you with a copy. If you can't be bothered emailing the author, then frankly you can bugger off and stop moaning. Secondly, accept that the changes you require to the academic publishing industry would be seismic, causing immense disruption. I'm not allowed to pop over to my nearest air-force base to have a go on a Eurofighter. It would be immensely disruptive, even though it was paid for with my tax. Similarly, you don't have the right to cause immense disruption to academics just to fuel your hobby.

However, I think there should be a much more simple solution. We should develop a system where independent people are capable of registering with their local university library. Perhaps for a small admin fee, this would give them an online library log-in, giving access to all the journals they want to read. I can't imagine this would be taken up by more than a tiny fraction of the population anyway. This seems like a far more simple system to set up, rather than insisting that we either destroy the publishing industry or spend 10% of the UK's science budget on publishing fees that we have no need to pay.

And if you have a problem with Elsevier coining it on the back of your research, don't publish with them. There are loads of journals that are run by various learned bodies (in my field, for example, GJI is published by the RAS, GRL by AGU, Geophysical Prospecting by EAGE, ERL by IoP). Any money made by these journals is pumped back into the subject by the learned bodies, funding conferences, research fellowships and the rest. So if you don't like the big publishers, find a journal run by a subject and publish in there instead.

Currently, academic publishing is dominated by the large publishing houses - Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell, Springer, etc. When I write a paper with new and interesting scientific findings, it needs to be published to enable my fellow scientists to read about what I've done, enabling them to use my findings in their research. The typical business model for a journal is as follows: most journals do not charge me a fee to publish (some do, but it's usually not too onerous). They make their money by charging people to read them. University libraries will buy subscriptions to the journals (usually they will buy 'bundles' allowing subscriptions to an entire publisher's catalogue), allowing all academics at the university to read the article. Meanwhile, a company wanting to access the research is more likely to pay the upfront fee for an individual article, which is usually about £30. Similarly, private individuals wanting to access the research will have to pay the £30 fee per article.

The dissatisfaction with the current model stems from the fact that the majority of scientific research in this country is funded by the tax payer (including my own). How, then, can it be fair that tax-payers are paying once to fund the research (out of their tax money), and then have to pay again as individuals to read the research? Many in the academic community view this as a morally untenable position - the public should have free and unfettered access to the results of all taxpayer-funded research (and when you read the comments sections on various websites, you really do get a sense of moral outrage).

I disagree with this argument. There are many things that my tax-money pays for, yet I can't just access for free. Our taxes go to the BBC, but I still have to buy a license fee to watch it! Taxes fund the NHS, but I still have to pay a fee for my prescriptions. Let's face it, some of my tax money goes to the army to buy tanks - that doesn't mean I have a right to turn up at the gates of my nearest barracks and demand a ride on a Cheiftain!

But, under the pressure of the academic community, the government, via the UK funding bodies, has buckled to pressure and is now about to make things far worse. They are planning to mandate that we publish only in open access journals. The business model here is that, rather than a 'reader-pays' model, we switch to an 'author-pays' model. Journal articles are made available for free, so instead authors are charged a much larger amount (typically £2000 or so). As far as I am concerned, this is a very bad publishing model!

What are the benefits of a so called 'gold' open access publishing model, where the author pays? Well, the sole benefit is that anyone, anywhere, can read your article for free. The negative is that this could add an extra 5 to 10% to the costs of of UK research. For example, last year NERC (my funding body) spend £180 million on research, and about 5,000 papers we published as a result. With gold open access of £2000 per article, this would be an extra £10 million, so just over 5%. Of course, the funding councils are not being given any extra money, so that means they will be able to fund 5 to 10% less research. In a time where our science budgets are increasingly stretched, and grant money harder and harder to come by, can this really be a good thing?

Secondly, we must consider the pressures this will place on the publishing industry. Currently, in a 'reader pays' model it is in the publisher's interest to publish only the best and most relevant research. A journal cannot afford to waste money publishing work that will not get read. Therefore, the commercial pressure is on journal editors to accept only the best work. Under an 'author pays' system, the only commercial pressure on the journal is to publish as much as possible. Quality is no longer a driving factor, because it doesn't matter whether things get read, all that matters is that there's lots of papers. So an author-pays model will simply lead to a significant reduction in the quality of articles that journals are prepared to accept. Putting this as simply as possible, there would be no reason for a journal to ever reject any paper, ever. I don't want to spend my time wading through a ton of crap papers to find the one or two good ones that I need. I want a journal to have already taken editorial decisions to only bring the ones that are of the highest quality to my attention.

What about the effects on libraries? Perhaps the libraries would be able to save money, because they wouldn't need to pay for so many journal subscriptions, and the money saved could be transferred over to cover author charges. However, this wouldn't cover all the back issues to which scientists need to access. Nor would it remove the need to subscribe to international journals to access work from people in other countries. Science is an international effort, so if the UK does something in isolation, it won't affect the need to pay subscription fees to read about work from every other country in the world.

Finally, what will be the impact on publishing academics. Obviously, the only barrier to publication will be money, so if you have money, you can publish, while if you don't, you can't. The model in mind is that university faculties will have central pots of money to pay for open access publication. So who will get the money for publication - the junior PhD student who has made a cool new finding, or the senior professor with his hand on the purse strings? At present, the quality of the paper is the sole deciding factor in where a paper is published. Under the proposed system, the deciding factor will be money. This would NOT be a fairer system, if would be significantly UNFAIR! I cannot understand how academics can be in favour of such a system.

The other proposed model is so called 'green' open access. This model takes the money out of the system entirely. Academics post their own content on their own websites (or possibly on a university-wide archive) or on archive sites such as the arXiv. To a certain extent, this system is already active, because many authors do post their work onto arXiv, and do post their papers on their own websites. Many academics see this as the model to which we should evolve. However, I think this is somewhat misguided, because the currently green open access exists off of the back of the mainstream publication industry, it cannot exist without it. Firstly, note that many green open access sites are heavily subsidised (as arXiv is by Cornell, for example, to the tune of about $500,000 per year).

More importantly, if I publish a paper in arXiv, it is not peer reviewed. Peer review as a process is vital to science, it makes sure only reliable results are published, and removes all the dross. I know it's not perfect, but it's the best system we have. The only way to get things peer reviewed is to submit them to journals, where they will undergo the full editorial process. Currently, journals are happy to provide this service, and publish the paper as their content, while allowing re-prints to be republished on author's websites, because it's not done widely enough to effect their margins. Just because a certain number of authors have put their papers on other websites, libraries are still forking out for subscriptions. If green open access became so widespread that it began to impact on the bottom line, I expect journals would begin to clamp down.

I guess this all comes down to whether publishers provide a useful service, or can we do without them. If they provide a necessary service, we should be prepared to pay for that service accordingly. If they do not, or if we believe we can achieve the same effects more cheaply, we should attempt to do so. Paraphrased from a comment on this blog, we need journals to provide (1) a decent and enforced peer review system, (2) an editorial system which can reject (or grade) papers (which provides quality control and therefore acts as a marketing tool) (3) a publishing system and (4) a citing system. The need for peer review is obvious, as is the need for a publishing system. Both cost money to administer. It is not free to put things on the internet - arXiv needs half a million dollars a year to function.

The need for a citing system is a key problem for green open access. Say I publish my paper, and put it on my website. Will it still be there in 15 years time when I have long moved on, or will a searcher simply find a broken link? It's vital that researchers can access older papers - journals provide the means of archiving them and an easy means to index and access them. This would not be possible with authors sticking their papers wherever under a green open-access system. The editorial and grading system is also vital, for both author and reader. Rightly or wrongly, as academics we are graded on the quality of papers we produce. When we can post whatever we like in an open-access mega-journal, it becomes very difficult to assess the quality of a academic's output (perhaps this is why so many favour this system). More importantly as a reader of papers, I much prefer to be able to look at the monthly output of my favourite journals, scroll through the list of papers that they have (which is a manageable list), rather than dive into a mega-journal and have to sift through all the dross to find some good papers. I'd rather pay an editor to do that for me.

Given these needs, how much will all these things cost? Let's imagine a typical medium-sized journal. They'll probably have about 5 staff: a senior editor to lead the editorial direction of the journal; two publishers to facilitate the peer review process - selecting the reviewers for each paper (or rejecting the really rubbish papers without review; an admin; and a guy to do the publication side of things. Plus within the publishing house they have the IT support and the rest. Let's say it costs £500,000 a year to cover everyone's salary, pension, computing costs, web archiving costs and the rest. This is a complete guess, but it doesn't seem like an exorbitant amount, right? In fact, this is probably on the low side. Well, for a medium-size journal publishing 500 papers a year, that's a cost per paper of £1000. So this must be paid either by the author, or through subscription. I don't see green open access as long term sustainable except on the back of a healthy publishing industry to bear most of the costs. As a commentor on the Guardian website put things rather well of the problems we'd face if we abandoned journals:

So, we come back to the question at hand, if we have to pay for a quality publishing industry, who should pay? For the reasons listed above, I think it should be the reader, not the author.

My thoughts on this are formed partly by my experiences while working as an intern at Shell. During my 3 months there, I must have downloaded at least 20-30 papers, paying the upfront costs each time. That comes to about £600-£900. Shell have a library system where you request a paper and they go off and get it for you, and they don't even (appear to) worry about the costs. I've no idea how much the average Shell employee downloads papers, but these are science-intensive companies, so I bet it's quite a lot. Whenever I meet employees, they all seem fully up-to-date with the latest research, so they must be reading it. This is money that goes back into the academic system, helping to contribute to a healthy publishing system that is necessary for research. And Shell are going on to use this research to make money. Under an author-pays model, they wouldn't have to contribute anything.

So what about the poor UK 'citizen-scientists', working independently, who want to read the latest research papers. These people are usually all over the Guardian comment pages complaining that they can't access research without paying. My first opinion is that they can't be that keen to read it - if you want to read a paper but can't find a non-paywall copy, your first port of call should be to email the author, who will likely be more than happy to furnish you with a copy. If you can't be bothered emailing the author, then frankly you can bugger off and stop moaning. Secondly, accept that the changes you require to the academic publishing industry would be seismic, causing immense disruption. I'm not allowed to pop over to my nearest air-force base to have a go on a Eurofighter. It would be immensely disruptive, even though it was paid for with my tax. Similarly, you don't have the right to cause immense disruption to academics just to fuel your hobby.

However, I think there should be a much more simple solution. We should develop a system where independent people are capable of registering with their local university library. Perhaps for a small admin fee, this would give them an online library log-in, giving access to all the journals they want to read. I can't imagine this would be taken up by more than a tiny fraction of the population anyway. This seems like a far more simple system to set up, rather than insisting that we either destroy the publishing industry or spend 10% of the UK's science budget on publishing fees that we have no need to pay.

And if you have a problem with Elsevier coining it on the back of your research, don't publish with them. There are loads of journals that are run by various learned bodies (in my field, for example, GJI is published by the RAS, GRL by AGU, Geophysical Prospecting by EAGE, ERL by IoP). Any money made by these journals is pumped back into the subject by the learned bodies, funding conferences, research fellowships and the rest. So if you don't like the big publishers, find a journal run by a subject and publish in there instead.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

If you are already a big name in your field, or you are a young researcher at a place like Harvard/MIT then you could wipe your bum on a bit of paper and put a photo of it on your website, and people would download it to look. But if you are a postdoc at a place outside the top 50 (or so) then noone is going to read anything you write unless it is published in a good journal; does anyone really think that academics are regularly checking the website of Podunk State University to see what their guys are doing?

The main role of the journal system is to filter papers based on their quality, so that the ones that are worth reading on average end up in good journals, while the ones that arent worth reading end up either unpublished or published in so low a venue that noone willl find them. This is a good system because it means that academics can just follow a handful of general interest journals along with the websites of those they know are good in their field, without having to wade through the tens of thousands bad papers that are produced every year. It also means that any academic will get their work widely read as long as they can get it into a decent journal; which would absolutely not be the case if we abolished journals.